Steele Sidebottom plays footy with a smile on his face.

And the Collingwood champion is smiling now after hearing, for the first time, the epic story of how the Sidebottoms came to settle in Australia.

It’s a tale that stretches back almost 200 years, encompassing a violent crime in England, a death sentence, a brutal term as a convict, some ill-gotten wealth that led to success in Melbourne’s early days, a remarkable gesture of love that improved the fortunes of an entire clan, and a mysterious name change that ultimately produced one of footy’s great names.

“It’s a nice surprise,” Sidebottom, 27, told the AFL Record.

“It’s blown me away a bit actually.

“It’s good to know about where you come from, but to have this pretty amazing story in your family just takes it to another level.”

It’s no surprise the Magpies vice-captain was unaware of his colourful heritage, given that traditionally his clan was devoutly religious and determined to whitewash ‘the convict stain’ and any suggestion of impropriety.

And, besides, many subsequent descendants had merely suspected there was ‘a skeleton in the cupboard’.

The AFL Record just happened to stumble across what was once a closely guarded secret.

Some time back when we revealed North Melbourne captain Jack Ziebell’s German ancestry, family historian Janet Hubbard mentioned we might be interested in highlighting the fascinating pedigree of another of her distant relations, Steele Sidebottom.

She gave us a copy of a self-published book about the Sidebottoms, and it was soon apparent there was a ripping yarn to tell.

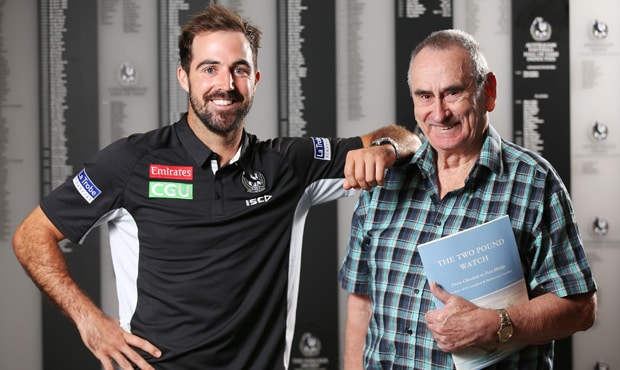

So we arranged for the author, Don Sutherland, to give the Pies star a family history lesson.

Retired engineer Sutherland, sprightly at 81, is a Melbourne fan but naturally takes a special interest in Sidebottom.

The distant relatives met for the first time at the Holden Centre.

Sutherland says they are fourth cousins, twice removed.

In other words, his great-great grandfather and Sidebottom’s four-times-great-grandfather were brothers.

Another brother is the reason for this story.

“Did you know your name should be Langford instead of Sidebottom?” Sutherland asked.

“No ... really? Jeez,” Sidebottom said, eyebrows raised. “Why?”

Sutherland provided an elaborate answer.

Their ancestors Thomas Langford and Mary Sidebottom married in the county of Cheshire, in north-west England, in 1798 and had 11 children (two of whom died as infants). The first seven were sons.

Their second-eldest offspring, William Langford (Steele’s four-times-great-uncle), inflicted great shame upon the family by committing a cowardly crime.

About 8.30pm on October 5, 1824, a Thomas Howard was walking home along a dark road near Manchester when, as The Manchester Courier later reported, a gang of up to six men “set upon him and knocked him down, some holding their hands in his mouth, and one knelt on his breast, while others rifled his pockets”.

The assailants stole Howard’s £2 watch, £10 in bank notes and some keys. A haul valued at more than $2000 in today’s money.

William and his mate John Barker, both 23, were arrested together and were in possession of some of the stolen bank notes.

Their accomplices evaded capture.

Strangely, William Langford told his captors his surname was Sidebottom – his mother’s maiden name.

“We don’t know why he did that,” Sutherland said. “It could’ve been to hide the shame for his family.

“It could also have been because his mother’s extended family, the Sidebottoms, had become wealthy in the cotton industry and he was trying to receive better treatment from the courts.”

If the latter was his motivation, he failed miserably.

The renamed William Sidebottom and Barker were charged with highway robbery – a serious crime made most famous a century earlier by English outlaw Dick Turpin.

They were held in atrocious conditions at the medieval Lancaster Castle for five months before facing court on March 5, 1825.

A jury found them guilty and they were sentenced to death.

This was soon commuted to life transportation, meaning they were forbidden from returning to England.

In the meantime they were forced to walk 370km in chains from Lancaster Castle to London, where they received odious accommodation on a prison hulk before making the arduous voyage to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania).

Sidebottom’s convict record noted he was single, stood 163cm (roughly average height) and had dark brown eyes and brown hair.

At the time of the crime, he’d been working with Barker as a labourer, but now claimed he was an ostler or stable hand in a clear attempt to avoid being assigned to chain gangs.

He took with him only a small box of personal effects, along with a seemingly unbreakable spirit.

The Medway, carrying 173 convicts including Sidebottom, arrived in Hobart Town shortly before Christmas 1825.

He was assigned to government contractors but soon found trouble, receiving two punishments of 50 lashes each from the dreaded ‘cat o’ nine tails’ for infractions including insolence, disobedience and threatening his master.

As a ‘mildly unruly and troublesome’ prisoner, he was sent to Maria Island, where he spent the next four-and-a-half years, copping another 100 lashes for stealing from a shipwrecked brig.

Finally on his best behaviour, Sidebottom was for a time assigned to farmer John Brown.

In 1835, he was granted a Ticket of Leave, which allowed him some element of freedom, so he moved up to Launceston where he formed a fateful alliance with ex-convict John Mills.

Mills was a publican and a brewer and Sidebottom learned a great deal from him.

There was a suggestion Sidebottom broke the law by selling sly grog to female convicts, and that the risk paid off because it made him flush with funds to pursue bigger business interests.

Sidebottom received a conditional pardon in January 1836 and it wasn’t long before he and Mills travelled across Bass Strait and took their chances in the new ramshackle settlement that became Melbourne.

Sidebottom helped Mills establish Melbourne’s first brewery.

He also enjoyed success with property deals, some of them dubious in nature, such as the one he struck with Melbourne’s founder John Batman over a block in Bourke St.

“It was a shady arrangement,” Sutherland said. “Batman was trying to hide his assets. He owned the land, but it was in William’s name. Batman died soon after (in 1839) so William got the lot.”

We remind Steele Sidebottom of this Batman link as we cross Batman Avenue to do a photo shoot by the Yarra River.

“Oh, this just keeps getting better,” he laughs.

William Sidebottom’s property portfolio included blocks in what are now prime positions in the CBD, including the £50 purchase of what later was the site of the original Coles store in Bourke St.

He also became one of pioneering Melbourne’s most successful publicans, at various times owning five hotels, including two in each of Bourke and Elizabeth streets, with names such as the Coleman’s Race, the Black Horse and the Golden Fleece.

“I might try to inherit some of it,” Steele Sidebottom quipped.

William Sidebottom catered for a variety of clientele, given one of his watering holes was hailed as “substantial and commodious” while another was labelled “a tavern of questionable repute”.

He was also one of just four publicans to operate at the first race meeting at Flemington in March 1838.

The next winter, at 38, he married English lass Emma Hale, who was just 15 or 16 – not an uncommon marrying age for the period.

The young bride, the sister of brewer Mills’ wife, descended from Sir Matthew Hale, Chief Justice to the King’s Bench in the 1670s, and was the daughter of a former British army officer who was wounded at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Sidebottom’s life continued to improve. A month after their marriage – Sutherland estimates it was only about the 30th to take place in Melbourne – he was granted an absolute pardon.

He could have returned to England, but life was too good to leave. Instead, he wanted his family to join him.

In letters home, Sidebottom offered to pay for their relocation to Victoria and to help establish them in their new lives.

His only condition was that they had to change their surname to Sidebottom, so he could avoid trouble for falsifying his name.

The proposal was eventually accepted by his elderly father and all but two of his siblings and their families. (His mother had died.)

The first to make the move was Steele Sidebottom’s four-times-great-grandfather Robert in 1840.

Robert had been just 14 when William was transported and they hadn’t seen each other for 15 years.

Steele Sidebottom shakes his head in disbelief at Robert’s huge leap of faith.

Robert initially left his wife in England and took with him their two young sons – the eldest died soon after arriving here but the youngest, Samuel, would be Steele Sidebottom’s great-great-great-grandfather.

Robert was soon running his benefactor brother’s large farm at Pentridge (now Coburg).

Another Langford/Sidebottom brother would travel to Melbourne alone, leaving his pregnant wife and six children in England while he paved the way for their arrival a year later.

However, it all ended prematurely for William.

On June 7, 1849 – only three months after the birth of his fifth child – William died at just 48.

He and his father (who died the previous year) were buried at the original Melbourne cemetery, now the site of Victoria Market.

Almost 25 years earlier, William was convicted of a despicable act and banished to the other side of the earth, but in many ways it was a blessing in disguise because it had provided he and his family with opportunities they couldn’t have envisioned in England.

We show Steele Sidebottom a photograph of William that was probably taken in the 1840s.

“Jeez, he’s got a better beard than I have,” he said.

Robert also thrived. When he died at 65 in 1877, he bequeathed a farm to each of his three surviving children in the Mickleham community he helped to establish.

“Your ancestor Robert was the only one who kept the Sidebottom name,” Sutherland told Sidebottom.

“The rest of them changed back to Langford.”

VIDEO: Steele's 10 goals. Watch a young Sidebottom put on a clinic in the 2008 TAC Cup Grand Final.

Robert originally changed his surname from Langford to Sidebottom, but after William’s death he preferred Langford-Sidebottom.

Adding to the confusion, subsequent generations of Robert’s (and Steele’s) line dropped the hyphen and used Langford as a middle name, and later Langford was dropped completely.

“If my name was Langford instead of Sidebottom, I wouldn’t have got all the smart comments about my name as a kid growing up,” Sidebottom said.

But ‘Steele Langford’ doesn’t quite have the same ring to it as ‘Steele Sidebottom’, which has always figured highly among polls for the best sporting names.

But not everyone was proud to be a Sidebottom.

Somewhere along the line, someone didn’t like how it sounded so they insisted, more than a little pretentiously, that it be pronounced ‘Siddy-b’tarm’.

There are no such airs about Steele Sidebottom, the country boy from Congupna, near Shepparton. He embraces the good and the bad of his family history.

And there’s another terrific crime link. Steele’s three-times-great-uncle William (John) Langford-Sidebottom modelled Ned Kelly’s famous armour at the outlaw’s Melbourne trial in 1880.

“This has been great,” Sidebottom tells Sutherland as they shake hands before we part.

“Don, if you didn’t tell me this stuff, I don’t think I would’ve ever found out.

“I’m looking forward to telling my old man and my (four older) brothers all about it. So thank you.”

“My pleasure, Steele,” Sutherland said. “After all, we are family. Albeit distantly.”

WATCH: A tribute to Steele. Teammates discuss the bloke they call 'Rusty'.

This story by Ben Collins appeared in the round eight edition of the AFL Record.

How Steele became a Sidebottom

Convicts, breweries and name changes - it's all part of the enthralling tale of how Steele Sidebottom got his family name.