This article, written by the Herald Sun's Glenn McFarlane, first appeared on forever.collingwoodfc.com.au in 2016.

Jack Dyer called it “a blind, unreasoning hatred” and it’s no stretch to say that the feeling is most definitely mutual.

Collingwood and Richmond do not like one another. One of the few things they have in common is the dislike for another one.

It hasn’t always been that way.

Collingwood initiated the motion that allowed Richmond entry into the VFL in 1908. But the defection of a Magpie star after his return from World War One drove a wedge between the two clubs – forever.

There have been fierce battles on the field and almost as many off it; a frenzied poaching of players that drove both clubs almost to the point of bankruptcy in the 1980s; and even fights on the suburban streets.

Ire for the Tigers hasn’t diminished. And here are eight reminders why:

1. DAN’S DEFECTION

Collingwood had plans for a Smith Street parade for its former captain Dan Minogue on his return from war in 1919. Those plans were abandoned the moment he told them he wanted to transfer to Richmond.

According to Collingwood coach Jock McHale, Minogue’s decision bordered on treachery, and the club strongly opposed the transfer. They even refused to pay out his entitlements from a retirement fund, such was the anger.

Minogue was forced to stand out of football for the rest of the year as Collingwood went on to win the 1919 ‘peace’ premiership, beating Richmond in a Grand Final result that seemed fitting for Magpies’ fans.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. Minogue, and Richmond, exacted their revenge a year later. He became the Tigers’ captain-coach and led his new team to victory over the Magpies in the 1920 Grand Final.

Richmond president Jack Archer’s pre-game speech lashed out at Collingwood for turning Minogue’s photo to “obscurity with its face to the wall” at Victoria Park. “Is that sportsmanship?,” Archer declared as he urged the Tigers’ players to come out and knock the Magpies off their perch, which they did.

It was a sweet victory for Minogue and a painful loss for Collingwood. A bitter rivalry had been born.

2. ROCKIN’ THE SUBURBS

Collingwood defeated Richmond in three successive Grand Finals (1927-29), but even through that time the Tigers still managed to get under the Magpies’ skin.

On the eve of one of those Grand Finals local police were called out to break-up groups of supporters of both sides engaged in a brawl. History, or local police records, fails to recall which team’s fans won the fight.

One thing that Pies fans of the 1920s would never forget was the manner in which Richmond “beat up” on Collingwood in one final in 1929. The Magpies had been unbeatable that season, and looked certain to become the first team to go through a VFL season undefeated.

But Richmond coach ‘Checker’ Hughes had other ideas. Before that semi-final he told his players: “Give them all you have got, and they will crack.”

From the outset, two of the Magpies’ most influential players, Syd Coventry and George Clayden, were flattened in “a reprehensible spirit that marred play all day,” according to one journalist.

One Magpie player, watching from the outer, said Richmond “tried to take out the Coventrys and Colliers”, and in doing so, was able to end Collingwood’s winning streak, with a bruising 62-point thrashing.

The loss deeply affected some fans, with the Herald saying: “several (female supporters) the ground sobbing … the male escort of one sobbing sister clumsily tried to console her … she turned on him like a tiger cat, and, as she stamped her feet on the footpath, shrieked: ‘We didn’t come here to see Richmond play, but to see Collingwood win.'”

Battered and bruised, the Magpies got one back on the Tigers a fortnight later, scoring a hat-trick of Grand Final wins.

Paul Licuria introduces himself to Wayne Campbell in round 16, 2002.

3. MEDAL MUDDLE

Three VFL players tied for the sixth Brownlow Medal, including Collingwood young gun Harry Collier, in 1930.

He had tied with Richmond’s Stan Judkins and Footscray’s Allan Hopkins, but Collier was unlucky not to have won the award outright, as one vote had been allocated to ‘Collier’ without referencing whether it was for Harry or his brother Albert. When pressed for more information later, the umpire said it was meant for “the little rover fella” (Harry). But the vote was deemed invalid.

The VFL initially announced there would be no winner. Enter Richmond’s VFL delegate, H. L. Roberts, who claimed the rules stated that “the player attaining the largest percentage of votes to games played (was) to receive the medal.” That was Judkins, who had actually been dropped from the Tigers’ team during that 1930 season.

The league then announced Judkins as the winner, to the disgust of Collier, and Collingwood. They felt an injustice had been done and it would take almost 60 years for that to be undone.

Always frustrated by Richmond’s intervention, Collier fought for years for retrospective medals to be struck for him, Hopkins, and other tied winners who missed out.

“Not meaning anything against Judkins, but comparing him to Hopkins and myself was ridiculous,” a candid Collier said late in his life. He finally got his rewards, a retrospective Brownlow Medal, in 1989.

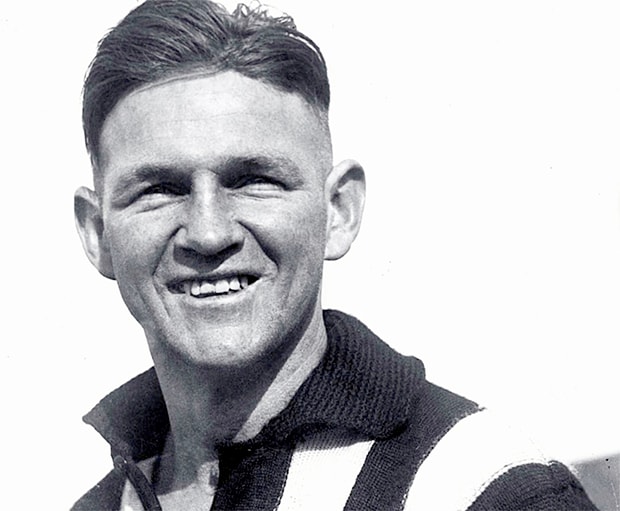

Harry Collier played 253 games in a Black and White jumper.

4. BOILING POINT

Tensions between Collingwood and Richmond reached boiling point in 1936 when a clash between genial goalkicker Gordon Coventry and Richmond defender Joe Murdoch drove another wedge between the two clubs.

Uncharacteristically, Coventry threw a punch at Murdoch. He was reported, chose not to reveal the reason for his retaliation and was cruelly suspended for eight weeks – for his first offence.

When the penalty was projected on the screens at the local Collingwood picture theatres, there were chants of disapproval from Magpie supporters.

The ban ruled Coventry out for the rest of the season, and not even some alleged post-game offers of inducements to Murdoch from John Wren or his associates could change the Tiger defender’s story.

“It nearly provoked a suburban war,” one Collingwood administrator said. “Wren was furious … (Jock) McHale thought it was a set-up. (But) he (Coventry) didn’t believe in squealing.”

Coventry had boils on the back of his neck, which Murdoch was said to have targeted. The administrator said: “Murdoch knew he had the boils. They belted him until he exploded, and he got eight weeks – for retaliating.”

Collingwood won the Grand Final that season, but had to do so without a shattered Coventry. The dislike of Richmond rolled on.

5. IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER

Jack Dyer hated Collingwood, and he saw the embodiment of the club as its coach Jock McHale.

He wished he could have played against McHale, and knocked his block off. But the biggest name in Collingwood’s history had long since retired when Dyer terrorised the suburban ovals of Melbourne.

But when McHale’s son, John, known as Jock Junior, came on the scene as a player during the 1940s, it gave Dyer his chance to upset the Collingwood coach, and to further infuriate the Magpie faithful in a game in 1944.

He would explain years later: “”My dream, and I dreamed it often, was to crush McHale. But it was an impossible dream. Then lo and behold!! One day Jock McHale did line up on me … in a Collingwood jumper and for four premiership points. At last … So it wasn’t the old boy … so what? It was the fruit of his loins.”

It would be the only time in Dyer’s career he would be suspended – for four weeks. But young Jock Jr., perhaps emboldened by having a few drinks at a wedding he had attended earlier in the day, gave back as good as he got. He threw a punch back at the Richmond strongman and copped four weeks as well. He probably figured it was worth it.

6. HART ACHE

The Magpies appeared well placed to finally shrug off those dreaded ‘Colliwobbles’ in 1973 when the club finished on top of the ladder.

But a loss to Carlton in the second semi-final dented the confidence and it meant Collingwood had to meet Richmond in a sudden-death Preliminary Final to advance to the Grand Final.

That looked a near certainty at half-time when the Magpies led by six goals, and with Richmond’s most damaging player, Royce Hart, sitting on the bench as the 19th man, under a serious fitness cloud.

At one stage during the second term the difference had even bloated out to 45 points.

The Tigers figured Hart could not play in the Preliminary Final and the Grand Final a week later due to knee issues, but club powerbroker Graeme Richmond insisted there would be no next week if Hart didn’t come on.

So the Tigers introduced him and he kicked a team-lifting goal early in the third term as the Tigers booted six goals to two for the quarter. It was a sign of things to come as they overcame Collingwood to win by seven points.

Collingwood had been unceremoniously dumped from the finals in straight sets with coach Neil Mann saying: “Once again we walk away from the MCG disappointed.” Hart had inspired his team; and Richmond fans wouldn’t let Collingwood supporters forget it.

7. THE FLOGGING

Collingwood was never expected to defeat Richmond in the 1980 Grand Final, having risen from fifth position at the end of the home-and-away season on the back of some old-fashioned grit and Tom Hafey magic.

But no one expected the nature of the loss.

It would be a then record Grand Final defeat of 81 points, a humiliation of epic proportions. Six goals to two in the first term set the tone for the Tigers and a 43-point margin was in place at half-time.

Kevin Bartlett was dominant with seven goals, David Cloke kicked six, and Collingwood’s seventh loss in a Grand Final since 1958 was a fait accompli early in the third term as a host of frustrated supporters left the MCG.

It was the sixth straight loss that Collingwood had suffered at the hands of Richmond in a final since 1969. Deflated Magpie fans wished the Tigers had the same sort of curse on them as Collingwood seemed to have, and so many years on, Richmond hasn’t won another flag.

8. POACHING WARS

The enmity between Collingwood and Richmond had a Cold War feel to it in the 1980s. It wasn’t quite the USA versus USSR – no one fortunately had fingers on the red button – but the hatred was as intense as it could be.

A poaching war in the early 1980s pushed both clubs almost to the point of distraction and financial ruin.

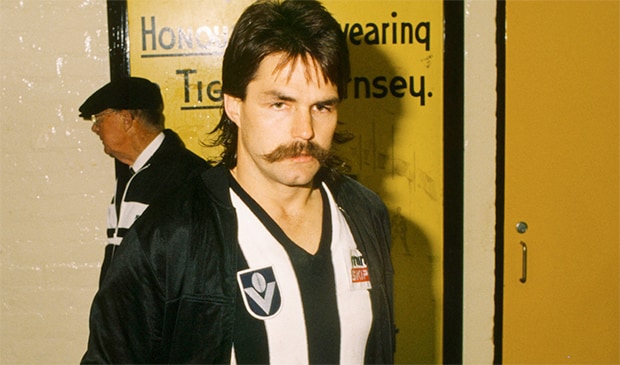

Collingwood fixed its sights on David Cloke, who had just turned 28, heading into 1983, and while Richmond resisted, the VFL Appeals Board granted the big man a pathway to Vic Park.

But it turned to full-scale war when Geoff Raines sought a release to join the Magpies after a contract standoff. There were legal jabs and a showdown between the two clubs, but Raines was granted leave for Collingwood.

The Magpies beat the Tigers twice that season. On one of those occasions the club’s banner provocatively read: “Out in the Woods, without a Cloke, and it Raines”.

But Richmond – the club and its football administrator Graeme Richmond – plotted revenge. They made a play for one of Collingwood’s favourite sons, Peter Daicos, and for a time the star Magpie gave it plenty of consideration before rejecting it.

But Phillip Walsh, Collingwood’s best first year player in 1983, was poached from under Collingwood’s nose. It was said Richmond “bluntly told the football world that cost was no obstacle” and Walsh and later Jon Annear were prepared to head to the Federal Court before ending up at Punt Road.

The Magpies hit back again in 1985 when it managed to secure Tigers forward Brian Taylor, who would eventually go onto kick a century of goals a year later. But for all the changes, what hurt the most was the financial bottom line. It was just another sign that these two great clubs –and their supporters – don’t like one another, and that hasn’t changed to this day.

David Cloke was at the centre of the poaching wars between Collingwood and Richmond during the 1980s.